A few weeks ago, my friend Sarah escorted me to her favorite bookstore in Omaha (shout out to The Bookworm), and recommended The Four  Tendencies. She’d read it and said she’d learned much about herself and also her students. Of course I wanted it for my own, and immediately she made me take “the quiz.” She was certain I was an Upholder.

Tendencies. She’d read it and said she’d learned much about herself and also her students. Of course I wanted it for my own, and immediately she made me take “the quiz.” She was certain I was an Upholder.

Wrong. I’m an Obliger.

What does this mean?

The Four Tendencies

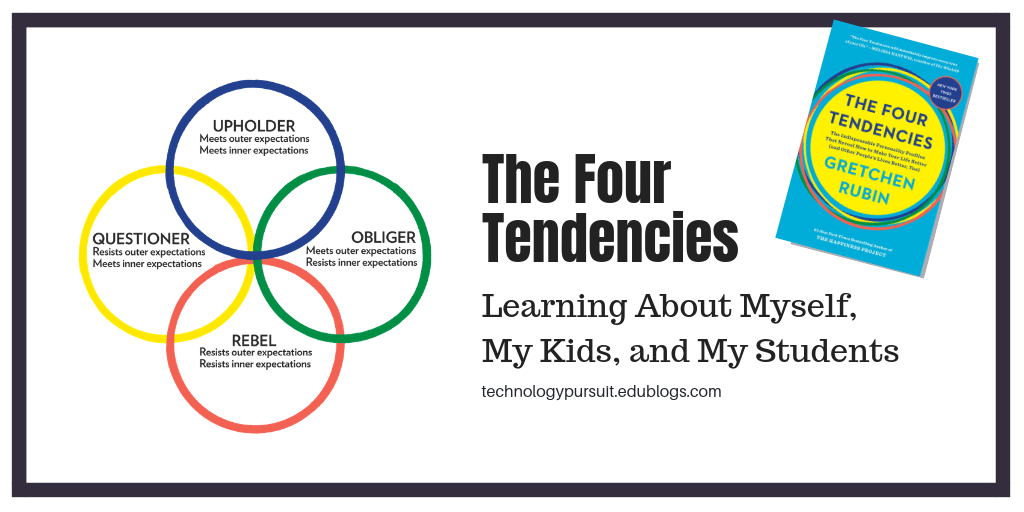

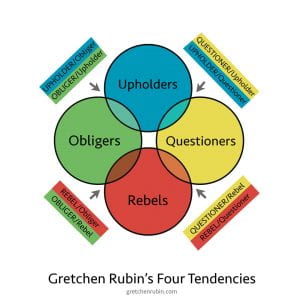

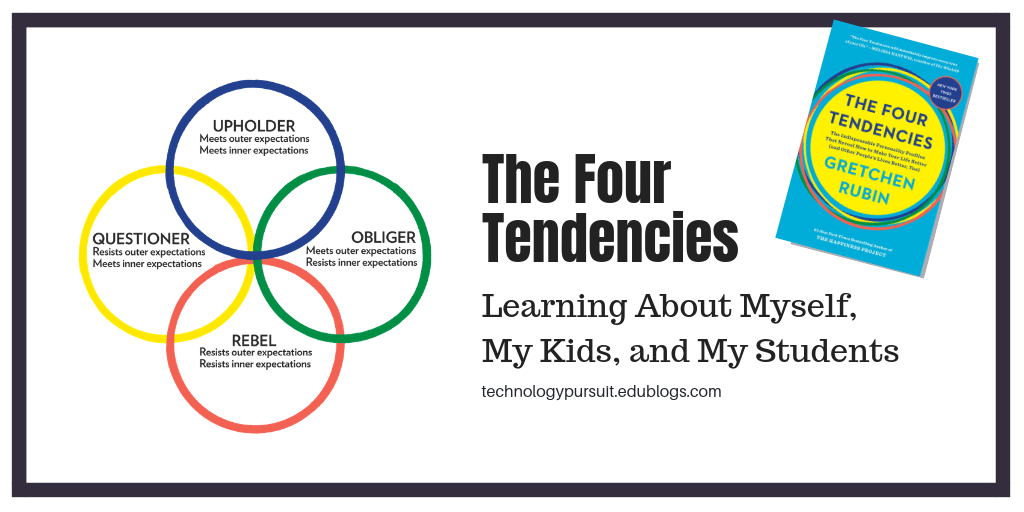

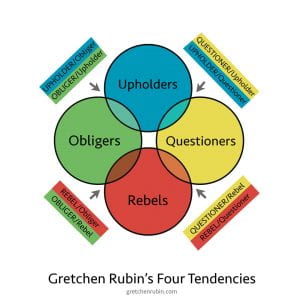

According to author Gretchen Rubin, who also wrote The Happiness Project among other titles, the Four Tendencies is a framework she created based on patterns she saw in human responses to outside expectations. In other words, Rubin asserts there are four main ways that we react to both outer expectations from others and our own inner expectations.

Upholder: These are the Hermoine Grangers of the world, the people who meet both the expectations of others as well as their own inner expectations. If they set a goal to exercise each day, they’ll do it. If they commit to planning a fundraiser for you, they’ll do that, too.

Obliger: This is me. Commitments to others are prioritized before commitments to myself. Obligers take care of outside expectations, make sure everyone is happy, and then will fulfill inner expectations.

Questioners: These people are opposite of obligers. They are fully committed to their inner expectations, but may not be so to outer expectations. This doesn’t mean they’re opposed to others’ expectations–they just need to understand and respect the why behind those expectations.

Rebel: Rebels resist all expectations–they want freedom and self-expression. This doesn’t mean rebels are lazy or don’t achieve–they will simply do so on their own terms.

What I Learned…

I’m an Obliger first, and then a Rebel second. I’ll work hard to meet deadlines that other set for me–and that also means that I work best when someone is relying on me. Deadlines I set for myself aren’t as threatening as deadlines others set for me. What Obligers like me need to do is seek accountability partners to help put the pressure on us.

However, I can turn into a rebel. This small part of me wants to defy expectations. Say I can’t do something, and it’s possible I’ll do it just because I can. I love independence and doing things on my own terms and in my own time.

More importantly, I think I understand others better, or at least appreciate where they’re coming from. Both my husband and I are Obligers, and we can be frustrated with our son, who’s a Questioner. He wants to know the “why” for everything–something we’d hoped he would grow out of but never has. But now I understand better how his mind works, and that he’s not trying to be difficult.

I can see some of these tendencies in my students, too, and more importantly, I can help work with them more effectively. Generally, Upholders and Obligers do well in the “game of school” because their tendencies fit well with meeting outer expectations of their teachers.

However, Questioners need to know the why, and teachers should be prepared for that. In fact, all students should know the why. Whatever we do in the classroom, we should be ready to explain what the purpose is and what the benefits are for those involved. Thankfully, we have Questioners to remind us about the importance of purpose.

Rebels, according to Rubin, are the smallest group, and I would venture don’t always succeed in the “game of school.” These students, and perhaps some questioners, have been my most challenging over the years. Rubin advises that we need to give rebels freedom and choice rather than demands threats.

Just How Scientific Are The Four Tendencies?

There’s not a lot of scientific validation on them. Rubin shares information about some research studies on the Tendencies here. It’s early, though. Like any theory that’s new–and especially any theory about human beings–take it with a grain of salt.

Rubin herself says that people aren’t completely one tendency or another–they’re more of a mix. I’m an Obliger-Rebel. My husband is more of an Obliger-Upholder. But I also wonder how a Tendency can change depending on a situation. Based on the framework, there’s no such thing as an Obliger-Questioner, but there are times, such as in conversations about education, where I can take on a questioner tendency.

Might it be interesting or beneficial for students to take the quiz? Perhaps. Being more aware of their natural tendencies could help them be more proactive to meet their deadlines, especially if they’re obligers and need accountability.

However, I’d also be wary of trying to classify students into black and white categories. Teens are still forming identities, and being human, they behave differently based on the situation.

I’d still recommend The Four Tendencies. It’s made me more cognizant about the different ways to share ideas to students and colleagues alike.