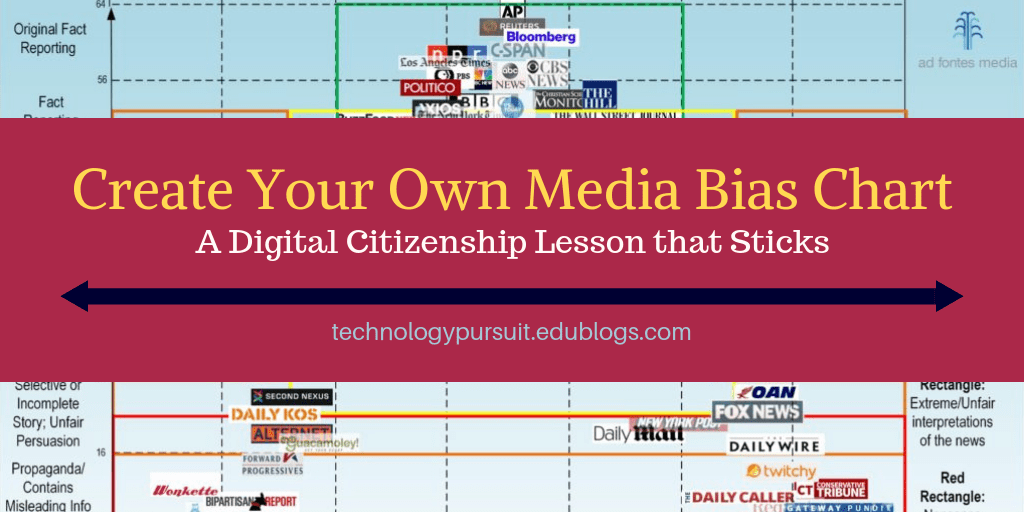

Chances are, you’ve seen this media bias chart (or similar ones) on your social media.

During my fake & biased news analysis unit, I wanted to incorporate this chart. I could have just had students study and analyze it, but I didn’t know how long-lasting the experience would stay with them.

Instead, I decided students could make their own charts.

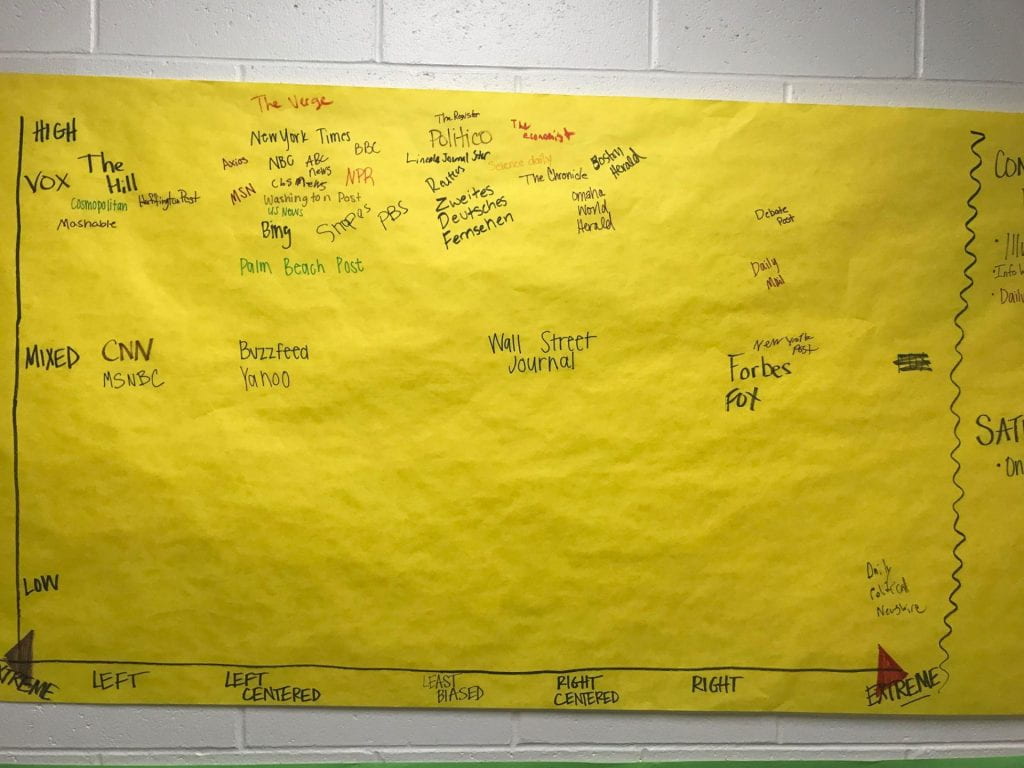

Using markers and butcher paper, I drew an XY axis. I also added a section on the side for sources that didn’t have a place on the chart (such as satire like The Onion).

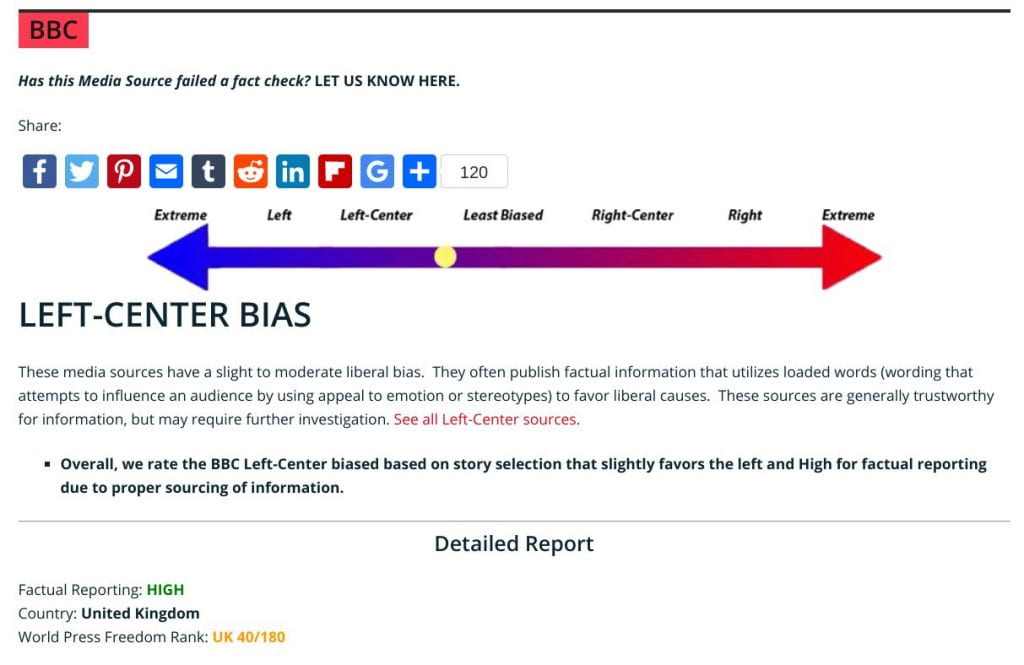

When class time came, I first modeled how to search for sources on mediabiasfactcheck.com, where students could then see how sources were rated. (See the BBC results below). Then I showed them how the chart worked–left/liberal sources on the left, right/conservative sources on the right, as well as the level of factual reporting.

At that point, the students started looking up their own sources. I asked students to find at least five sources–and they needed to move quickly because if their source was already on the paper, they had to find another one.

At that point, the students started looking up their own sources. I asked students to find at least five sources–and they needed to move quickly because if their source was already on the paper, they had to find another one.

I also encouraged students to check sources that they see on social media, and to Snapchat and YouTube they went. Of course, many searched mainstream sources or sources their parents used.

What did they find from this? Our mainstream media tends to the political left. However, we live in a conservative rural county, so many also realized that many sources they see on their social media feeds tend to the right side of the political spectrum.

We ended with discussing how every form of reporting has some bias. Any news passed on is slightly skewed through the reporter’s perspective, but as the chart shows, some sources choose language and stories that lean left or right politically. We also talked about how this chart doesn’t indicate which sources are right or wrong, good or bad–except for the extreme ends of the spectrum, which are downright fake news and faulty reporting–but that the goal is to be balanced in our research and reading. If you use a source that leans right, then also peruse a source that leans left.

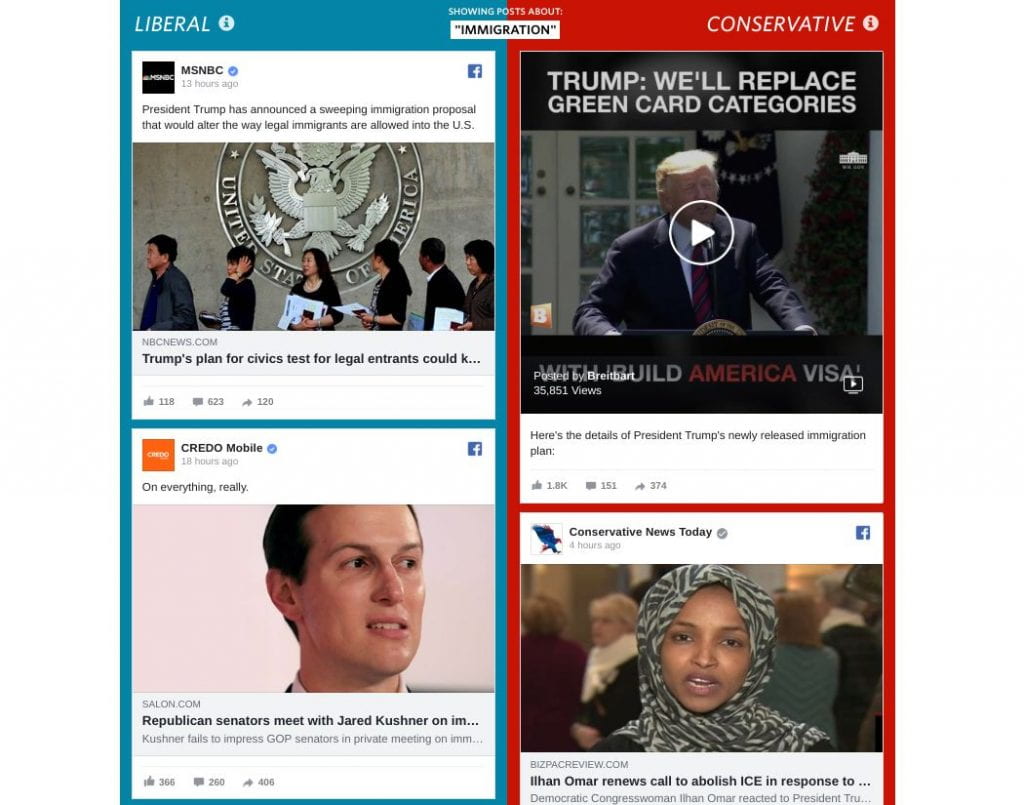

Another great source (if your school doesn’t block Facebook like mine does) is Wall Street Journal’s Blue Feed/Red Feed. It’s a great comparison of what our social media feeds can look like if we program them to see only left-leaning or only right-leaning sources. This encourages discussion on how this can affect American’s understanding of both sides of issues, as well as the effects it could have on our society if we refuse to listen to those who think and believe differently from us.

Lessons and resources like these are essential to make our students critical thinkers about the media they consume and their responsibility to society. The media bias continuum activity, in particular, was one that students commented said had a major impact on how they viewed the media.

Any other resources you love using to encourage critical thinking about media consumption? Share them below!